Notice, that’s “need” not “want”. There’s a difference.

It’s going to be a good day for solar power!

This post grew out of a well-received seminar I’ve been presenting at RV shows. And that seminar itself grew out of my responses to lots of email questions from our readers that went more or less like this:

“How many solar panels do I need to run my air conditioner?”

Now, I’m not an electrical engineer (I’m aerospace), and I don’t work in the solar power industry. More importantly – I’m not a solar power salesman. What I’m about to walk you through is a process and some (hopefully fun) analysis that will help you properly size a solar energy system for your RV without wasting money on stuff that’s very cool but you probably don’t need.

This doesn’t mean I haven’t wasted my own money on cool stuff that I don’t need! Just to give you an idea of where I’m coming from, here’s a quick rundown of the electrical system on our Class B Winnebago Travato, Lance:

- Lithium Batteries: Lance currently has a 525 amp-hour Lithium Iron Phospate (LiFePO4) battery from Lithionics. The battery self-manages, and has thus far self-maintained. We’ve never wanted for battery capacity since installing it.

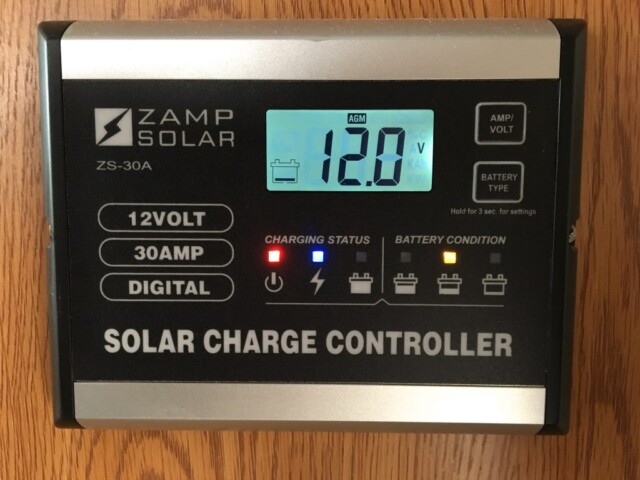

- Solar Panels: We currently have 300 watts of solar panels on the roof. These are run through the factory-installed combiner, and are integrated through a 40 amp solar charge controller from Zamp. We started off with one 100 watt panel.

- Second Alternator: The coach and chassis electrical systems on our coach are completely separate. There’s a second alternator from Nations Alternator which powers the house system and charges the Lithium battery.

- No Generator: We got rid of this because it was extra weight and we just didn’t need it. Most times, even when hookups are available, we don’t bother to plug in.

- Inverter: We have a Xantrex Freedom SW 3000 inverter charger which takes the place of our generator. This is the second inverter we’ve had in this coach.

Along the way and while tearing the rig apart multiple times, I’ve learned a thing or two, and that’s what I’m going to share with you in this post. So now, let’s get back to that question. Grab yourself a coffee or something – this is going to get lengthy.

How Solar in Your RV Works:

“How many solar panels do I need to run my air conditioner?” implies a basic misunderstanding of how solar energy in your RV works. For example, this is NOT how it works:

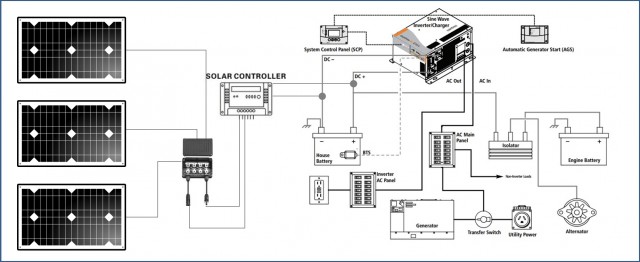

At least, that’s not how it works if you want air conditioning on a partly cloudy day. The solar panels are actually just a part of a much larger system, and a simplified diagram of that system might look like this:

There are really two important concepts to pick up from that diagram above. The first is that solar is just one of several potential energy sources that you’ll find on a typical RV. In addition to solar, you might have a generator, shore power, and a vehicle alternator. All of those will put electrical energy onto the “mini grid” that you’ve got in your RV.

The second thing to note in that diagram is that it’s all about the battery. All of the sources putting power onto your grid can be either “on” or “off”. For example, solar power is “off” at night. The alternator is “off” when you’re not driving. And so on. The only thing that’s there for you all the time is your battery. The battery is what stores the energy produced by the other sources so that you can have power once the sun goes down, once you’ve turned off the ignition, or during generator quiet hours.

These two concepts are important to understand, because once you start thinking of your RV’s electrical systems as a mini grid with some storage; you’ll be able to define an objective for your solar energy ambitions. If you start making tech purchases without defining an objective first, you can drain your wallet (and your batteries) in a hurry. Don’t ask me how I know this.

Our Objective for Solar Power in the RV

In as simple terms as I can put it, this is what we’re trying to accomplish:

We want our solar energy system to recover the energy we’re using day-to-day, but no more. You see, there’s a key difference between home solar energy systems, and RV-based ones. In an RV, you can’t sell your excess energy production back to the power company. All you can do is store it in your battery.

But once your battery is full, it’s full! You can’t fill your battery over 100%. So if you build your RV solar energy system bigger than you need, you’ll wind up with a lot of wasted potential. (That’s actually a nerdy joke, because the Volt is the SI unit of electrical potential. Give yourself 50 bonus nerd points if you got it!)

Besides wasted potential, you’ll also have some wasted money from building your RV solar power plant too large. And I don’t know of too many people who like wasting money. So now that we know we want to “right size” our solar power investment, we need to figure out how to balance that equation. We’ll start with the left side of the equation: charging sources.

Charging Sources in Your RV

If you remember from the schematic, there are several potential charging sources in your RV. Yours may or may not have all of these:

Alternator: If you have a motorhome, or a towable RV with a beefy umbilical connection, you can count on driving or running the engine to provide you with power. The amount of power you’ll get from this varies according to the size of your alternator and what other electrical loads you’re running. On the high end, a dedicated second alternator like ours will produce around 180 amps of power when it’s running. At the other end of things, a stock alternator on a smaller vehicle may only have 40 amps of power left over to charge batteries.

Even if you don’t have a beast like this, your alternator is a powerful source for charging your batteries.

Shore Power: Here, obviously, you’re tying into the larger electrical gird which (hopefully) doesn’t shut off. But shore power runs at 120 volts and your battery stores at 12 volts. To convert things from one voltage or another, your RV will employ a “converter” (not a terribly creative name) or an inverter/charger. These devices have various capacities. A stock RV converter may be able to deliver 40 amps of charging to your batteries, and a high-end inverter/charger like ours is self-limited to charge at 100 amps.

Generator: If your rig has a generator, this too will charge your batteries. They typically do this by providing energy to your converter or inverter/charger (not by connecting to the batteries directly). In addition to the converter’s capacity limit, the generator itself has a capacity limit. This can be only 2000 or 2500 watts for smaller generators. So if you’re running the air conditioner, two TVs and a blender with the generator, there might not be much left to go into the batteries.

Solar Power: Solar panels are sold in varying sizes, but a 100 watt panel is a commonly found size – particularly for RVs. That panel is rated at 100 watts at peak efficiency – meaning on a 78 degree cloudless day at solar noon on the equator during the equinox. I don’t know too many people who RV under those conditions. (Come to think of it, I don’t know if those conditions actually exist outside a laboratory.) But for the sake of argument, if we assume the best case, that 100 watt solar panel can provide just over 8 amps of energy for charging. With 300 watts on our own rig, this means at peak, I can expect to generate 25 amps of charging if I’m lucky.

Here’s what’s really important about all that. RV solar is the least powerful of the charging sources typically available. We’ve just reviewed the charging sources you have on an RV, and seen capacities from 180 amps all the way down to 8 amps. Using our rig as an example, what this means in real-life is that I will generate as much stored energy in one hour of driving as I will with over 7 hours of peak solar generation. (180/25 = 7.2)

Some Usage Scenarios

This doesn’t mean solar power doesn’t have a place in your RV. Maybe it does. I’m not trying to dissuade you from purchasing solar panels, and I’m certainly not implying that solar panels aren’t cool. But I do think that before you dive into an expensive solar project, you should give some thought as to how you use your RV. If you don’t use your rig in a way that lends itself to a solar solution, you may want to rethink things. Let’s look at some typical RV usage scenarios and I’ll try to explain.

“I use my rig almost exclusively at RV parks or campgrounds with electrical hookups available.”

In this case, I’d argue you have little use for solar power. Even a basic 40 amp converter will provide more charging than five 100 watt solar panels, and it will do it night and day, rain or shine. Adding solar in this scenario won’t get you anything except lighter pockets.

“We do more ‘touring’ than ‘camping’, and so we drive most every day.”

This actually applies to Stef and me. In this case, the driving will charge your batteries more than solar ever will. You’ll likely find that your batteries are full or near full most of the time from driving. This is another scenario where the addition of solar won’t really add much.

“We do a lot of ‘boondocking’. Parked, away from utilities, and not moving the rig most days.”

THIS is the ideal use case for Solar energy in an RV. If you’ve got no hookups, and you’re not driving, solar power starts to look a whole lot better. Yes, you can run the generator (if you have one), but people generally don’t like the noise and the fumes if they’re avoidable. Solar power can help you avoid exactly that.

You’ll need to consider how you use your own RV, and what charging sources you have available. From that knowledge, you can make an informed decision as to what role RV solar can play in your rig. Assuming you’ve done that, and you’re going ahead with solar power, there are some common terms we need to understand, so let’s look at that next:

Watts, Amps, and Amp Hours

Solar panels are typically rated and sold in Watts. Electrical loads are also typically rated in Watts (you can usually find the wattage stamped into any electrical appliance). But RV batteries are typically rated in amp-hours. Since we’re trying to equate things from an energy in = energy out perspective, we need to be able to convert things easily. Fortunately, the equation is pretty easy:

Watts = Amps * Volts

Volts are the unit of potential, and amps are the unit of current. Their product is power.

If you’ve read this far, you probably know that you have two kinds of power in your RV. 12 volt DC from the batteries, and 120 volt AC from the grid or generator. Watts are how you can equate them. A Watt is a Watt is a Watt. The voltage might be different, and also the current, but using Watts will get you from one to the other. So, for example, a current of 1 amp at a potential of 12 volts is 12 watts. A current of 8.33 amps at a potential of 12 volts is 100 watts. So remember the 100 watt standard solar panel? When it’s feeding your 12 volt RV battery, it’s producing a current of 8.33 amps.

(For the rest of this article, I’m just going to assume 12 volts for a battery. Yes, I know it varies by battery type, state of charge, etc. etc. I’m just keeping the math sane.)

Battery capacity is typically expressed in amp-hours. A Group-31 battery might have a capacity of 100 amp-hours . This just means you multiply the two together, like this:

amp-hours = amps * hours

So a current of 1 amp flowing for 1 hour will produce 1 amp-hour of charge. And that 100 watt solar panel – at peak efficiency – would produce 8.33 amp-hours of charge in one hour.

It’s important to get this down because with RV solar, what we’re really talking about is using it to charge the RV batteries. This kind of math tells us how much. But that’s as tough as the math gets in this post. So if you’re not a math person, and you’ve made it this far, breathe a sigh of relief and let’s move on!

RV Solar Power System Components

I know this seems like a lot of background before we get to the answer, but this is stuff you need to know. Some of these things might even save you money.

Batteries

There are two main types of battery chemistry that you’ll find in RVs today. The first of these is lead-acid. These batteries have been around forever, and though there have been new ways to dress it up (AGM batteries, Gel cells), they’re all basically the same chemistry for the purposes of our discussion.

A typical AGM battery

The other type of battery that’s becoming popular in RVs is the lithium-ion battery. These use a completely different chemistry from lead-acid batteries, and they require a different charging profile. They’re also much more expensive than lead-acid batteries. There are lithium battery chemistries that are safer than others, and those are the ones that belong in your RV.

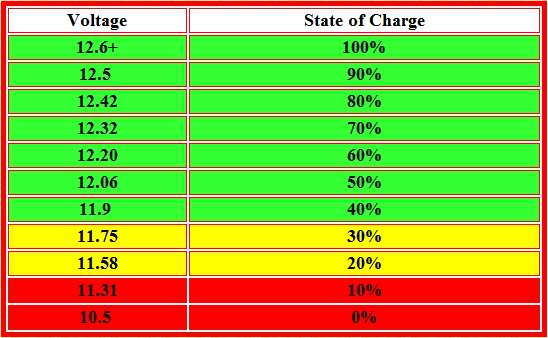

But it’s far more likely that your RV has some type of lead-acid battery than a lithium one, so that’s where we’re going to focus our examples. Sadly, batteries don’t come with a “Gas Gauge” to tell you they’re 5/8ths full. It’s sad because that’s exactly the information we’re going to need. So to get that info, you’ll need to use a State of Charge Chart. They look something like this:

While I don’t know exactly what you’ve got in your rig, I’m willing to bet that somewhere in your RV there’s a display panel that will tell you the voltage of your batteries. Using the state of charge chart is simple: you just find your voltage, and the chart will give you the percent full your batteries are… ish. So if your battery voltage is 12.1 volts, the chart will tell you that your batteries are between 50 and 60% full… ish.

(It’s most accurate to read your battery voltage when the batteries are “at rest”. That means with no charge being applied, no current being drawn, and having sat that way for a half hour or so. But if you can’t generate those conditions, it’s OK. It’s a pretty inexact science anyway.)

One more piece of wisdom about lead-acid batteries and we’ll move on. To get the longest life out of your batteries, it’s best to observe the “50% rule”. This means that you shouldn’t discharge these batteries below 50% if you can avoid it. They won’t blow up or anything if you discharge them more. But you will find yourself replacing them sooner.

Solar Panels

There’s a lot of technology around solar these days, so let’s get some basic terminology and options out of the way up front.

Monocrystalline vs Polycrystalline

When you’re browsing for solar panels, you’ll quickly realize they come in two types. Monocrystalline and polycrystalline. Does it matter which kind you get? Maybe. They actually look different, too, so let’s start with that.

This is a picture of polycrystalline solar panels. Polycrystalline panels are about 13-16% efficient. And they’re the less expensive of the two kinds.

These are monocrystalline panels. You can tell the difference because the monocrystalline panels have a typical square-ish/stop sign appearance. They’re made from a more pure silicon, and so these panels are 15-20% efficient. Since they’re more efficient, that means they can be physically smaller and you still get the same output. They’re also more expensive.

We actually have both kinds of panels on our RV right now.

I’ve played around with them a bit. While monocrystalline panels are theoretically better in low light conditions, and better in high heat conditions, I can tell you that I’ve tried and I can’t discern a difference in our RV. Perhaps if I had a solar installation covering a couple acres, those small differences would start to add up to something you can measure and take to the bank. But in an RV, your install won’t likely be big enough for you to tell.

What I DO notice about monocrystalline panels is that they are physically smaller for the same output. If you’ve got limited roof space available (like we do on our class B), then this can be a big benefit. But if you’ve got the room, a 100 watt monocrystalline panel and a 100 watt polycrystalline panel will give you the same 100 watts.

Money Saving Tip:

Unless you need the reduced size of a monocrystalline panel to fit on a cramped roof, save yourself some money and use the cheaper polycrystalline panels. There’s no moral superiority in the monocrystalline panels, and your toaster won’t know the difference.

Flexible vs. Flat Panels

Recent years have seen the advent of flexible solar panels. These panels claim to be lighter (they are), more aerodynamic (they can be), and easier to mount to your rig since you don’t have to drill holes (also true). But in my book, the big advantage of flexible panels is that they can conform to curves. They’re also more expensive.

Traditional flat panels on the other hand are less expensive and have typically longer warranties (25 years vs. 10). They’re more durable, hence the longer warranty. Flat panels are also mounted off the surface, which allows cooling airflow underneath and improves efficiency. They can also be tilted to point more directly at the sun. On our own RV, I’ve only used flat panels.

But – straight flat panels sticking off the roof of a vintage Airstream would look terrible! So with that in mind, here’s another…

Money Saving Tip:

Unless you have a unique situation that calls for the aesthetics of a flexible panel, flat panels are a more durable and less expensive way to get the job done.

To Tilt or Not To Tilt

(If you’re that vintage Airstream reader, you can skip this section.)

OK. This is an Air Force base and not an RV, but the idea is the same.

If you’ve got flat panels, you may have the option to tilt them to point them directly at the sun. The tilting is usually accomplished with some sort of hinged rack and support system. Pointing panels directly at the sun is more efficient – but how much more? Well, the answer involves trigonometry, but I’ll spare you that and skip ahead to the answer:

If a panel pointed directly at the sun is producing 100% of its possible energy, then a panel 25 degrees off axis from the sun is producing 90%.

Yep. 90%. For a 100 watt panel, that amounts to less than an amp under typical conditions. It’s not much. And in order to maintain peak efficiency – you would have to climb a ladder several times a day and jockey panels around. Your reward for that effort would be a whopping extra 6 minutes of TV.

Meh.

Money Saving Tip:

Don’t worry about tilting or rotating your panels. On an RV-sized system, it’s more trouble than it’s worth. On a utility-company sized system, the gains are worth the expense and effort, but on the roof of your rig, you’ll likely never notice.

The Solar Charge Controller

Typical solar panels put out somewhere between 16 and 20 volts, depending on a lot of things. Your RV batteries are nominally 12 volts. A solar charge controller is basically a voltage and current regulator that keeps your batteries from overcharging. Every RV solar installation has one. There’s more than one way to accomplish this regulation, and so there are more than one type of solar charge controller.

PWM Controllers are more or less the standard ones available today. It’s the kind we have in our RV, in fact, that picture above is the model that our Travato shipped with.

MPPT stands for Maximum Power Point Tracking. These controllers represent the ultimate in efficiency at 94-98% (meaning, most of the energy from the panels finds its way onto your RV’s “grid”). MPPT controllers are also better at dealing with a low state of charge, long wire runs, or really cold days. Unfortunately, that efficiency comes with a matching price tag. So if none of those special conditions apply to you, you can guess where this is going.

Money Saving Tip:

Unless you’ve got a huge system, long wire runs, dead batteries, or like to RV in the dead of winter, just go with a PWM controller. The more expensive MPPT controller won’t likely be worth it.

Estimating Solar Output

So with that math and terminology out of the way, let’s flesh out the left-hand side of our equation a little more. That’s the input side.

You can buy a 100 watt panel, but you won’t get 100 watts out of it. The reason for this is that there are a LOT of factors that can impact the energy recovery of a solar power system. Here are just a few:

- Time of Day

- Panel Tilt

- Weather/shade/sun/clouds

- Dirt in the air

- Dirt on your panels

- Efficiency of components

- Temperature (Contrary to intuition, solar panels work best at cooler temperatures. A 100 watt panel at room temperature is an 83 watt panel at 110°.)

So with all those things affecting the solar energy output, how are you supposed to get a handle on how much energy you’ll get? Well, if you like to take the easy way out, you can just go with this rule of thumb:

A 100 watt panel will generate 30 amp-hours per day

It’s a rule of thumb, not a perfect calculation, but it’s pretty useful nonetheless. The number will be higher in the summer, or further south. The number will be lower in the winter, or further north. But if you like to work in nice round numbers – 30 is your number.

If a rule of thumb isn’t good enough for you (and I don’t blame you), there are other tools you can use. Google “solar position calculator” and you’ll find all sorts of tools that will tell you the azimuth and elevation of the sun at any point on the globe on any given day. Some of these tools are even pretty fun, and it’s easy to waste a full day playing with them (trust me, I know).

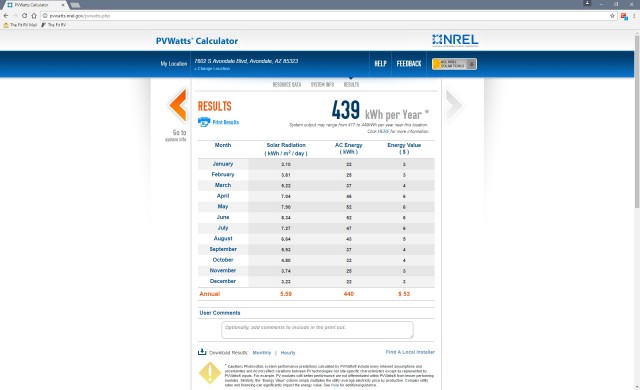

But by far the best tool I found is actually put out by the US government (I know! Right?!), and it’s free. The National Renewable Energy Lab has an online calculator that will predict how much energy you can recover with a given sized solar energy system, at a given location, on a given day. It uses historical weather data and lots of math to give you a simple answer to the “how much energy will I get” question. You can find it here:

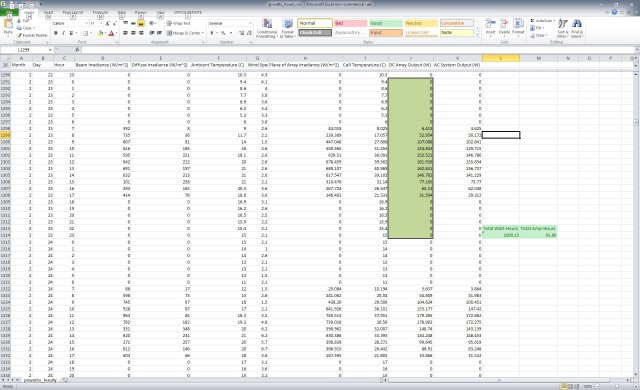

To check it out, I used our own RV. I entered a system size of 300 watts of fixed panels, mounted horizontally flat, at Phoenix International Raceway (where I gave this seminar last). It told me I could expect a total of 439 kWh per year from such a system.

But I tend to think of my RV energy usage in days instead of years, so I broke it down.

439 kilowatt hours * 1000 = 439,000 watt-hours per year

439,000/365 = 1203 watt-hours per day

1203 watt-hours /12 (volts) = 100 amp-hours per day

100 amp-hours per day /3 panels = 33 amp-hours per day per panel

Which is remarkably close to the 30 amp-hour per day rule of thumb. Since we were estimating in Phoenix, the 10% increase should be expected.

But the NREL website goes beyond that! It will allow you do download the data – day-by-day, hour-by-hour, so you can predict your energy output on any given day. On the day we were in Phoenix (February 23), I downloaded the data and the NREL website predicted I would generate 91.6 amp-hours of energy. I compared this to our actual output, which was 78.8 amp-hours for the entire day. That’s about 14% low, but certainly still in the ball park. The difference could have been attributed to clouds, perhaps I didn’t park exactly level (though I certainly try) or any number of other factors.

The NREL website is good enough that I’ve given up trying to calculate solar output in any other way. I either go with the rule of thumb or jump right to their calculator if I’m contemplating a trip to Alaska or something. I recommend you do the same.

The Load Side of the Equation

Now that we’ve got a decent idea of how much energy we can expect to come in from an RV solar energy system, let’s turn to how much energy will be going OUT. There are a few ways to do this, but most of them are no good.

Approach #1:

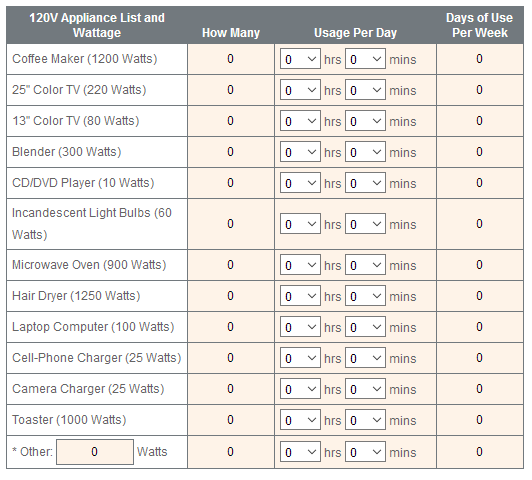

If you’ve poked around the internet on this topic for a while, you’ve no doubt come across energy calculators. These present you with a number of appliances or other electrical loads and you estimate how long you’ll run each load. From there, it creates an “energy budget” for you. They look like this:

These suck. Every single one of them. Don’t use them.

You’ll usually find these “helpful” calculators on the websites of merchants selling solar panels. That should be somewhat of a red flag.

The main problem is that – let’s be honest – you have no idea how long each day you run your hair dryer, or how many watts it uses! Sure, maybe if you look you can find that it’s rated at 1500 watts, but does it really run at 1250 watts? I don’t know! Well, jeez, we’d better be safe and estimate high then, huh? And my toaster? How long does it run? Well, that depends on if I want one piece or two, and how dark I want my toast. I’d better put down 30 minutes just in case everybody wants four pieces of toast. And the stereo? Well I don’t run it every day, but I might. I’d better put down 4 hours just to be safe…

You see where this is going. Garbage in – garbage out. These calculators, without fail, will cause you to overestimate your electrical needs and buy more solar panels than you really need. Don’t go there.

Approach #2:

This approach is slightly better, and something I’ve actually done myself, but I don’t recommend it. It involves taking actual measurements in your own RV.

To do this, you’ll need a way to measure current, both AC and DC, and a lot of patience. I did this on our own rig, and you can find the results in this post I made on calculating the 12 volt loads in our RV. But again, I don’t recommend this because it’s tedious, time consuming, and you’ll still wind up estimating how long you want to run your toaster.

Approach#3:

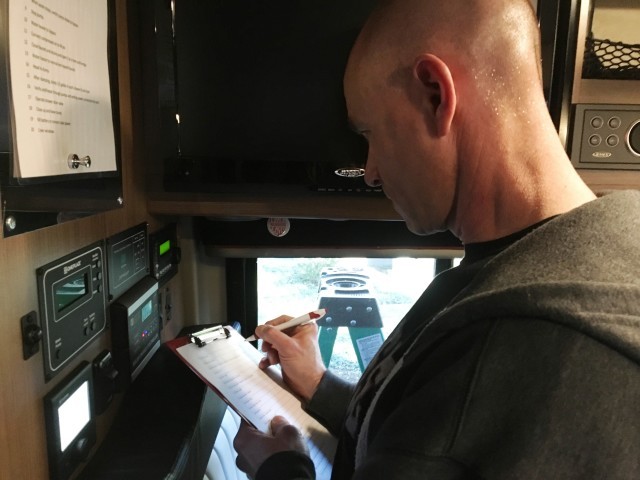

This is BY FAR the best, most accurate, easiest, and most fun way to measure your electrical loads. You just go camping and do your thing. I call it “camping in the name of science”. Stef doesn’t buy into this, but that’s what I call it. Here’s how to run your camping experiment:

- First – go do your normal camping thing. It’s important to have as typical a trip as possible. Don’t try to conserve. Don’t try to use extra juice. Just be yourselves.

- Once the experiment starts, no generator usage. If you have solar panels on your rig already, unplug them. If you have a motorhome, don’t turn on the engine. The idea here is to only draw down your batteries – not charge them as well.

- You want to start timing the experiment at nightfall, and you want to start with full batteries. So run your generator up until sundown. The reason for this is simple: Solar power doesn’t work at night. And if you don’t have enough power to make it through the night – you have a battery capacity issue, and all the solar power in the world isn’t going to help you.

- Start timing once the generator is off, the sun is down, and the rig is unplugged. Use the rig normally.

- Keep tabs on your battery. You want to know how long it takes to drain your batteries down to “empty” (keeping in mind the 50% rule if you have lead-acid batteries).

That’s it! Way more fun than crawling around your rig with a multimeter. Here’s how an example might work out.

If your typical RV day involves getting out of your rig – then do it during your experiment!

Let’s say you have a 200 amp-hour battery bank. They’re lead-acid batteries, so you don’t want to discharge them any more than 50%. At day zero, you start at nightfall with a full battery bank.

At the end of 24 hours, your voltage is down to 12.4 volts. That’s still about 80% according to the state of charge chart, so you continue on.

At the end of the second day, your voltage is down to 12.2 volts. 60% according to the state of charge chart, so you keep going.

At the end of the third day, you’re down to 11.9 volts. That’s 40% on the state of charge chart, so you stop the test and turn on the generator.

So – in three days, you used 60% of your battery capacity.

Your battery bank is 200 amp-hours. 60% of that is 120 amp hours over three days.

Dividing that by three, you used approximately 40 amp-hours per day.

DONE!

Putting it all together

So now, you’ve got a handle on the supply side of the equation, from either the rule of thumb, or from the NREL website. You’ve also done an experiment to determine exactly how much energy you use on a typical day. So let’s translate that into how much solar you need to equip your rig with.

Continuing with our previous example, we’ll assume we use 40 amp-hours per day of battery capacity. We’ll also assume that we’re good with the “rule of thumb” of 30 amp-hours per day from a 100 watt panel.

40 amp-hours per day = 30 amp-hours per panel per day * X panels

Divide both sides by 30 and you need 1.33 100 watt solar panels.

Now, I’ve not seen a 133 watt solar panel for sale. But I have seen plenty of 160 watt panels. There are a lot of starter kits that include them, like this one (I’m not affiliated – just found you an example). So, from our camping experiment, we’ve determined that a 160 watt panel will keep our batteries topped off most days, and that kit fits the bill.

Parting Thoughts

A couple thoughts on the solar power thing before I wrap up. Even after you’ve gone through the experiment and analysis above, there are still some questions to ask yourself before you invest in RV solar. For example:

- Will I ever be staying in one place for three days with no movement and no hookups? In the example above, even without solar, the RV didn’t encounter a battery capacity issue until some time into the third day. If you never stay put for three days, solar power in that situation isn’t strictly necessary, as the alternator will charge you up as you drive to your next destination.

- Do you have the propane and holding tank capacity to match? In other words – does it do you much good to have 100% full batteries with 0% fresh water?

- And finally, were there simple conservation steps you overlooked? Could you replace incandescent bulbs in your RV with LEDs? That would save a lot of energy and tip your equation. Good, old-fashioned conservation may get you where you need to go without the investment of time and money in RV solar.

So there you have it. I hope this hasn’t come across as a “Solar Grinch” piece. We’ve got plenty of solar panels on our own RV and we think it’s awesome. We’re in favor of clean, renewable energy wherever we can get it. But I’m not in favor of wasting money, and often I hear of people maxing out solar capacity on their brand new rig without a clearly defined need for the expense. I don’t want that to be you.

(It can be me though. This stuff is like toys to me… 🙂 )

Cheers!

Thank you for all the information! It was so well written, even I could understand it! Here’s my situation: We’re in Northern NH and starting to dream about camping season. We have an older camper. It’s a 1993 Layton 26′ tagalong. However, she wasn’t built for solar. We have started working on modifications (she’s permanently parked to boondock. Like a second home that’s off grid). The first year we got a “portable” 100w system and hooked it up to the 2 6v golfcart batteries she came with on the front (these do the basic systems). Seemed to work great to keep the fridge cold during the week when nothing else was in use & fridge was set to lp. If we wanted to use anything off the 110v side (microwave, tv, AC, wall outlets), we had a generator. Last year, we decided to add more batteries, another 100w of solar, an 2000w inverter (cheap one from Harbor Freight), and take her off the generator. We got 4 6v AGM batteries (305ah each on the label) hooked up in series and parallel. Didn’t last 24 hours with only the fridge and 2 phones charging 🙁 And they were hooked up to the panels and charging during the day. I’m thinking I just don’t have the battery capacity to make it last? I would have thought that 610ah would have been plenty, however we are in the Northeast, not great sun, not spectacular temperatures, and trying to run a not so energy efficient camper off 4 6v batteries.

I would agree that you’ve probably got a battery capacity problem. If you can’t make it through 24 hours on the self-test procedure, you may want to look at additional capacity, or making your camper more energy efficient.

Love this article and the one estimating power needs!

Any comments on the portable solar kits available for purchase? Is the efficiency the same? Lifetime?

What is the expected lifetime on a solar installation, and any concerns about appropriate disposal at that point?

Thanks!!

As far as the portable kits… a watt is a watt is a watt. So as long as they’re rated honestly, your decisions can focus on space available, storage requirements, etc.

Solar panels can have really long warranties. 25 years or more. Of course, nobody in the RV solar field has been out there 25 years yet, but it gives you an idea as to the confidence the manufacturers have in their gear.

This was awesome!

Hello, What seems to be missing for me from your ***oh ever so helpful post*** is that I will be running a laptop and an airfryer while in this real life test.

That means I’ll need to buy an inverter (not converter?) to get 110V. Which one should I buy?

Then once I find out my needs, by measuring the percentage use, I will have a solar panel power idea.

Thoughts?

Yes, if you intend to run 120 volt appliances off the grid, you’ll need either batteries and an inverter, OR a generator.

We’ve had good luck with Xantrex and Magnum inverters in the past. Victron is also top quality stuff.

Get one sized to handle the concurrent loads you expect to run.

Some 120v appliances are energy hogs, so if you plan to run one with an inverter from your 12v bank, make sure you have enough reserve amp hours. A general rule of thumb is to multiply your 120v amps from an inverter by 10 (ten) for the 12v amps consumption. So a 1500 watt appliance conceivably consumes about 15 amps at 120, or about 150 amps of 12v. My 200a golf-cart battery array at 50% discharge would be discharged in less than an hour – or about 45 minutes. That’s more power than we use for the whole coach for an entire day – led lighting, phone and tablet charging, an led flatscreen, charging a couple of ebikes, etc.

For running these types of appliances or our roof air conditioner, we run the built in onan generator – it puts out 40 amps of 120 volt power – enough to run the AC AND a 120v high-energy appliance. It’s quiet and powerful and uses about a half a gallon of fuel an hour.

Our 160w portable solar panel ‘suitcase’ can be placed anywhere in the sun with 20′ power leads – we get about 8ah of charging out of them. Enough for most day’s 12v power usage. I just installed a 600w inverter and a couple of outlets it powers, for light usage. It’s good for 540w continuous usage – from Xantrex. High quality stuff.

YMMV

Plenty of reserve capacity here!

That’s the great thing about these batteries.

We’ve run the air conditioning from battery – in the desert at 110 degrees – for over 14 hours.

And the batteries keep about 10% of their power in reserve anyway… just in case.

James,

Thank you for the excellent walk-through on solar.

We had our new Jayco 24RL out for its maiden voyage last week here in Montana. We have a GoPower 30 amp solar controller, one 190 watt solar panel on the roof, two new AGM batteries and a GoPower 3000 watt pure sine wave inverter. Conditions were: cool and cloudy 2 of the 3 days, partial shade (30%) on the sunny day. We ran minimal lights, no microwave, refrigerator on propane, etc. There is some latent draw from gas monitors, smoke detector, radio, etc. About 2 amps.

Throughout the day, I noticed that the batteries would generally be at around 11-12 volts most of the time.

We dry camp almost exclusively for 2-5 days at a time, spring-end of summer. We have sufficient propane, fresh water and tank capacity for that.

I am considering Dakota 100 ah 12 v lithium batteries. The reason I’m considering the lithium batteries is that they will produce power for a longer period before discharging. I believe my solar charging load would be approximately 29 ah with 3×190 watt panels.

What is your opinion on my setup and the idea of lithium batteries + 2 more 190 watt panels? I have no problem running the generator, but would like to avoid it if I can purely for the aesthetic value of quiet camping.

Not a bad plan. I’d do it in stages. Get the batteries first.

You describe your electrical needs as pretty minimal. If one solar panel will keep the batteries topped off, would you still want to get two more? You won’t get more than 100% full!

The lithium batteries – even if they are the same size as your AGMs, will get you almost twice as much usable capacity. I’m not familiar with the brand you mention, but start there and then evaluate.

Well done James.

Like many, I have a problem with space on the top of my 31′ Tioga. Vents and other things are installed haphazardly on the roof which makes installation of the same size panels impossible.

That said, what is your advice about using different size pannels to accommodate available space and if the answer is ‘yes you can’, what is the best way to connect them: Parallel or Series or a combination of both?

Appreciate your response.

You can use different size panels, but how effective they are will depend on how you connect them, and what their individual specs are. It’s a bigger question than I can answer in a comment, but it’s a GREAT question for a future post or video! Look for a post this summer on exactly this topic. (We have to get our new RV first before I can make the video!)

Hi guys, I read your article about solar panels… Thank you, lots of good info. My question is… I have three wet coach batteries. Adding solar (or any charge)… I assume they can only take a certain amount of amps over a certain amount of time to charge properly. How would I know how many amps is the most efficient to properly charge them quickly? I assume this is the big problem with electric cars… You want to charge them fast but you can’t just keep adding power. TIA

Interesting question. It’s been a while since I’ve dealt with lead-acid bateries, but really, the information on charging them should come from the battery manufacuter.

Trojan, for example, puts out a detailed guide that you can find here: http://www.trojanbattery.com/pdf/TrojanBattery_UsersGuide.pdf

Usually the charging for lead-acid batteries runs by voltages, not amperes.

Amps will be limited by whatever component is doing the charging. Your solar charge controller or converter. So if you have a 30 amp solar charge controller, obviously, you don’t want to add any more panels than that.

HTH!

This is definitely the most comprehensive article I’ve seen so far. To echo what most everyone else has said, you definitely have a knack for communicating this stuff! I can see why you teach seminars on this.

I’ve got a few questions too. I am trying to determine how much solar I will need, but I don’t actually have the RV to test things out. I’m building a trailer and want to at least set up the electrical correctly the first time. My game plan is to install two100Ah AGM batteries and two 250W solar panels. I figure I can go back and add extra batteries and solar panels as long as I plan appropriately. But, I’m getting a little confused with the whole 12v and 110v conversion thing.

I’ve heard that a watt at 12v is the same as a watt at 110v. Can you explain more on the conversion from wattage required by your device to battery Ah to inverter/converters to wattage required by solar panels?

Also, is it an issue to use cheap polycrystalline home-use solar panels? I can get new 250W solar panels locally for about $60, which is significantly cheaper than any “RV” solar panels (15-20V?). For example, someone is selling 395W solar panels with a open circuit voltage (which I read somewhere was the key factor) of 49.5V. So as long as my inverter can handle 48V, is using those type of panels an issue?

First – open circuit voltage matters. Whatever panels you get, you will want to make sure they are compatible with your solar charge controller. A solar charge controller intended for RV use may be only intended for 18-20v panels. Panels intended for mobile use may also be built to handle the rigors of life on the road, versus sitting in one place forever.

Solar panels do not directly feed your inverter. It does not matter if your inverter can handle 48v. Your inverter will be drawing from your battery bank.

Yes, a watt is a watt is a watt. An inverter will change watts from 12v DC watts to 120v AC watts. But you lose some along the way. The particular losses will depend on the inverter, but may be in the neighborhood of 15%. A converter or charger changes watts the other direction – also with losses.

I’d recommend consulting with a solar electric system designer as a sanity check before moving ahead.

Good luck!

Hello James. Thanks for the great article. I’m just starting on my journey of research before deciding whether I want venture into RVing in general, and this has been super helpful.

Since this article is going on 4 years old, I wonder if there’s been any updates on technology or costs in this space that are worth calling out?

Things are pretty much still the same – as in I would take the same approach to determining how much solar I’d need.

There have been new panels, etc. But the basics are still solid.

Haven’t changed my mind about pointing panels or MPPT etc.

Hello!

What a great article! Seriously, you explain it for the simple mind and that’s appreciated.

Quick question.. how do I charge my solar with the alternator?? This may be a dumb question being that I’m not sure it’s possible, but I’m admittedly not too good at this stuff.

I have 300W solar, with 2000W pure sine inverter, and 200Ah lead-acid battery bank, for what it’s worth.

Thank you in advance!

-Alister

Well, to be completely correct, you never charge the solar panels. Everything charges your batteries.

As to charging your batteries with your alternator… on a motorhome, that should be happening for you from the factory. On a towable RV, you’d need some sort of umbilical connection to make that happen – basically compatible wiring that would go from your towing vehicle (where the alternator is) to the towed RV (where the battery is).

Good evening,

What a fantastic tutorial! Thank you so much for this. I have a question about calculating my needs. I currently do not have batteries that I can rely on to do a “boondocking” test. They are old AGM and are pretty much shot. I do, however, have a Power Watchdog by Hughes Autoformer. I currently run a hog of a rooftop AC that draws roughly 15 startup amps and runs at around 10-12 amps. We will NOT be using the rooftop AC when we travel. We have since purchased an LG mini split (27 seer, 15.8 eer) 9,000 BTU. This should use considerably less energy.

With that being said, would it be possible to just check my readout on my power watchdog for 24 hours? It keeps a continuous reading of KWH. I kept track one 24-hour period and I used about 30KWH. If I convert that to amp hours, an online calculator told me it was 300amp hours. Does this sound right? It sounds really high to me, however, we did run the rooftop AC a little on purpose as to see what our consumption would be. We will be traveling to hot areas regularly and will be using AC often. Hopefully the mini split will help with less consumption.

Thank you in advance.

I’m not familiar with the Power Watchdog. Does it track both 120v and 12v loads, or does it only track 120v? You’ll need both if you’re going to run 120v appliances through an inverter.

Hey James,

What a great write up! Thank you. With a 5th wheel and a residential refrigerator we have started to dry camp and manage our power. Needless to say that the 3 yr old <180Ah two battery factory setup which has long expired we decided to go with 900Ah of AGM 6v batteries and will be starting with a 100w solar panel to see what we need. We are excited about where this will take us!

Your section on going out and surveying normal use to determine solar need is brilliant. We will do this through the 20/21 winter in TN to see what it brings. I expect to drop by with questions from time to time but I have to say that if one needed to filter through all the minutia out there on the web on RV solar, your site and your explanations is the filter we need! Thanks so much for the clarification and simple explanations for so great an insight.

Happy trails. Be safe.

KC

Wow! I’m so glad you found it useful.

Best of luck with your “camping in the name of science!”

I live in Australia but I can apply most of your information to my own RV situation. Absolutely brilliant and I’ve learnt a lot. Thanks James.

Glad you found it useful. The sun is the same… here or there!

Stay well down there!

Hello James,

I have a 45’ renegade motorhome and want to install solar, we do a lot of dry camping in Glamis ca, (sand dunes) for 4-8 days at a time. I was looking at 300w panels (maybe 2) to help not have to run generator as much. It’s a12k diesel so not bad on fuel but over a weeks time it adds up. My stove and microwave runs off 120 so I thought two big panels would help replenish the battery power used to run the microwave story time or stove to heat something up. I have a magnum control panel that tells me what my batteries are doing and other stuff along with auto start function, also a 2500 or 3000w inverter, but I believe if I still need some kind of sulfur monitoring panel along with a couple circuit breakers. what would be the best solar monitor (I think you call it) to get. Just trying to figure out everything I would need to hook it up.

Thanks John.

It sounds like you’re building a reasonable shopping list, but I’d recommend consulting with someone like AM Solar in Oregon. This is what they do every day!

I am wanting to set up a boondocking system on my 50 amp fifth wheel with 2 rooftop 13k btu A/C units. We are in southern AZ and run our A/C a lot. What would you suggest?

2 rooftop AC units are going to use a lot of power. You may find that the battery capacity required to run that setup for any length of time would be prohibitive.

You could put a lot of solar on a fifth wheel, but for something like that, I’d consult with someone like AM Solar in Oregon.

Okay so we camp out in the Co area. We bought a new Forest river that comes prewired with Solar amp. My question is I have a 50 amp service that I can split into a 30/and 20. The 20 controls just all me electrical plugs, one ac and charges battery. All I want to do is get a invertor to work with a solar panel that will operate just the necessities, such as keep battery charged, use wall plug for charging phone and wife Hair dryer. and electronics for the water pump and control panel . How can I figure that out?

Great info!! It’s stuff that you think about and you have it all in one blog! Totally agree with how you figure out how much solar you need. You have to have that base to start from so figuring out how much/long battery you use to get to 50% over time then that will tell you how much solar power you need. It may be you are doing overkill with it. And always good to have alternative power sources because you never know what can happen. Also having more efficient appliances can help or even conserving if needed. What are ways you can conserve power or make them more efficient? Especially with air conditioning as that seems to be what most people are interested in. I’ve heard that installing a mini split is a lot more efficient than the typical rv AC units? That is if you have a place to install it?

I have been considering adding solar panels to my motorhome house batteries but am concerned how the other charging systems (From the alternator or 30 amp inverter would affect them. Thought I would have to install an off switch from the solar panels so that when the batteries are being charged from other sources, electricity wouldn’t flow back into the controller or panels and damage them. If I am understanding your article correctly, a solar controller would prevent that, therefore I can leave the solar panels hooked to the batteries all the time even when they are being charged from other sources. Just want to be sure!

Unless your solar charge controller is of some defective kind I’ve never heard of, you should not have to switch it off if you are also charging from another source.

(My word – that would be a pain! Turning it on and off each time you started the engine? No Thanks!)

Initially we were looking at a custom adventure van from Outside Vans but after learning the price tag we started researching other options. Your channel has helped us decide on purchasing a used Travato 59K.

Being a newcomer to the Van/RV world my current concern is the power setup based on our needs. Without the real world experience a load calculator is the only option I have to figuring out my power needs. I couple web sites indicated we would need 60-90 amps a day. My numbers could be off, just not sure.

Finally my Questions

1) Can I assume the Travato is setup to use the one chassis alternator for charging, provide around 30 amps/hour?

3) Zamp Solar setup can max out at 420 watts of solar? In a perfect world this would provide 35 amps/hour to the battery?

4) When driving in sunny weather would I get the 30 amps from the alternator plus the 35 amps from the solar for a combined total of 65 a/hour?

5) I would love 200 usable amps. Can I simply switch out the AGM battery for a 200-amp Lithium Battery? I found an article that does this very option but I need to switch out the Charger/Converter unit to handle a Lithium Battery. Would love any insights

Some answers:

1. Yes, the chassis alternator will charge the house battery. I never ran any tests on the rate, which would depend on a lot of other things (temperature, what else you have running, etc.)

3. 420 watts does represent 35 amps at a nominal 12 volts, but it’s extremely unlikely you’ll ever see that kind of current coming in. Maybe at solar noon on a cloudless day at the equator on the equinox. Better approach is to use one of the methods outlined in the article.

4. Solar does not stop while you drive, so yes, the charging is additive. However, due to 1 and 3, I doubt your absolute number is accurate.

5. There are a number of drop-in lithium replacements. I didn’t go that route, so I can’t speak to how well they work. But for best results, you would want to update all your charging sources (converter, solar charge controller, and alternator) to something with an appropriate lithium profile.

Wow amazing!!, thanks

So what ah battery can i buy for 100w or 300w solar panels and the repective inverters with the solar regulators

You should size your battery based on the *load* you want to power and how long you want to power it. Not on the equipment you have to charge it.

Assuming we do not “hook up” in campgrounds and if stationary for 3-5 days, and if our small camper is only using 2 LED lites at nite 3 hrs max, and the fan in the propane heater runs a few hours a day, can I just hook up a remote, satchel type 120 w solar panel directly to the battery with wires, for say, 3-4 hours, thereby skipping installing the solar charge controller? Is the charge controller 100% needed? Or could I use a portable volt meter, test the battery, and use the handy chart to estimate voltage/remaining charge?

You can’t hook a solar panel up directly to the battery and expect it to work.

(I mean, you could hook it up, but I don’t know what will happen. Probably nothing.)

You need to solar charge controller to get the voltages right for bulk/absorption/float. Otherwise, the voltatges are unregulated.

I flew model radio controlled airplanes back in the day (100cc-10ft wings) and used a solar panel to charge the battery directly. You will overcharge the battery and boil the acid out of the battery. I ended up installing a mechanical timer and would set it for one hour to charge the battery when it was down to 12.1 volts. I used it that way for 4 years with no problems.

Thank YOU! I was all over the net trying to figure out the “so what” questions about RV solar installations. You-know? So what that you get this much power, so what that your frig uses such and such power, so what, so what, so what. The big questions are how all these items of information affect us in installation and on the road when dry docking.

It was wonderful to find all answered here. BIG DEAL. Again, thanks!

Glad you liked it!

James thank you! Your article is great packed with alot of information. For sure has caused me to rethink my how I’ll go about my rv power needs.

Thanks again,

Gene

I don’t think there are words to express how helpful this article was and is to me.. I’ve been starting to get into solar but never could get anyone one to break it down or explain it the way you did.. I’ve been off the grid living and tired of the generator

Absolutely brilliant tutorial, James! Thank you so much for simplifying the mystifying (not to mention overwhelming) world of solar energy!

Thank you so much for the simplification of the process for a “newbie”.

When dry camping, I am plugging my trailer shore power into my inverter to run the Microwave and the plugs. I turn off the breaker for the converter when the inverter is running. Am I making a big mistake doing it this way?

Well, I’m supposing it works, but the possibility of a loop if you forget to flip the breaker is kind of scary.

I think if I had to do that, I would unplug the converter, just for good measure.

I’ve never really thought of whether this was safe or not. Perhaps others will chime in.

I built an automatic switch box using an electrical contactor, which is like a relay but for alternating current. Calling it a circuit is an overstatement, it’s an electrical contactor mounted on a short DIN rail in an electric project box with 4 wires running to it. The sensor side of the contactor is connected to the AC cord into the van, leading to my inverter. My inverter has a built in transfer switch so the AC flows from the inverter to the panel either way. The switching side of the contactor is connected on the wire running from the electrical panel to the converter. If the van is plugged in, the contactor senses AC power coming in and it switches to allow power to flow to the converter/charger. Conversely, if the van is not plugged in, the contactor switches to prevent power from reaching the converter. Everything works perfectly, I can still use the panel breaker to turn the converter/charger on and off, all of my outlets get either shore power inverted power, but when the inverter is proving the power there is no way for the converter to charge the batteries.

First, this is the best analysis of solar I have seen. Second, kudos on it’s longevity, over two years old and still relevant and still getting comments. The thing I like most is taking into account the contribution, or lack of, for fresh water, propane, etc. as well as assessing behavior. Thanks for a great article!

Thanks, Jeff!

I’m right there with Jeff. This is the best, plain language, fun, easy to understand article on solar i’ve read, (& i’ve read a few). The picture of the sun, panel, ac, camper was exactly where my brain was going lol!

I’m now going to read lots more of what you’ve written in preparation for picking up my new toy on Tuesday!!!

Thanks 🙂

really good job on solar. l have a 26 ft 5th wheel that l take hunting and camping , l stay 3 to 4 weeks at a time no a/c power. my battery will (2) will last about 2 1/2 weeks then the generator. Ques is will a 2 amp solar panel keep up. l use lights at night and morn for about 1 hour and frig, water pump now and then. most all cooking and wash is outside. thank you

Well, anything is better than nothing. If your batteries are lasting 2.5 weeks, that’s pretty darn good. A 2 amp solar panel is only like 24 watts or something. If you’re going to bother adding the infrastructure for solar, then I would go with a larger panel. A 100 watt panel is a pretty basic size.

You sound pretty conservative. Who knows. With 100 watts, you might get a whole 4 weeks!

the only reason l asked about the 2 amps is because it was given to me for xmas and it is still in a box and l don’t know what else to use it for. thank you for the advice

I also agree this is a very good article on solar. I’ve played with solar power since the early 80s, powering a small cabin in the Teton valley and 280’ deep solar well pump.

For the last two decades, life got in the way, but after retiring jumped back into my old hobby. We’ve been RVing in a small 5th wheel (24’ class) and I installed 4 – 100W panels. 3 flexible on the roof and 1 rigid for manual tracking. Through 3 (mostly boondocking) trips varying from 35 – 45 days each, I find your rules-of-thumb right-on.

I started with two standard lead acid RV/marine batteries (paralleled at 12V) and a 30A Morningstar Prostar MPPT controller. By our third trip, I modified the system to 2-100W flex panels and 1-battery. Other than the first day when we we plugged in at an RV park to “summerize” our trailer, this system kept our battery topped by evening of every night (except the last two). We rely on the battery for lights, water pump, furnace fan, device charging. Our lp tanks lasted the whole trip, (refilled one, but never emptied the second).

We stayed 7-10 days at stretch. the story on the last 2 days involved trying to scale Vail Pass in late May in a snowstorm. 12” of snow, two days in Frisco at Heaton Bay CG and no hookups. Below freezing every night so the heater fan used a lot of battery. Our panels were covered with snow, but the controller still reported 2.1 Ahr generated over the 2 days stuck until the pass was clear down to Denver.

I agree. Don’t over build it.

James, this is all great information and here’s my challenge. I have a residential frige. and my wife likes to watch tv at night even when we’re boondocking. I currently have 640 watts of solar on my roof and I still have to run my generator 2 times a day, the last time being 2 hours before quiet hour to fully charge batteries for overnight. Normally I’m down to 12.2 V by the morning. I have 4 L16 batteries which are quite large and rated at 380 A H at 20 Hrs. What can I do to make it through the night without my battery falling so low? What about wind generator tied in with my solar panels?

Honestly, short of plugging in or running a generator, there are only two things you can do: Decrease your electrical demands, or increase the battery size.

It sounds like your batteries should be large enough for the task. How old are they?

heh James i just got a 2019 TRAVATO 59GL and love it , we do mostly boondocking and so wanted to add a 3rd solar panel on top to plug in the ready to go plug….we have the standard 140 and a 100 panel i think on top from factory Winnebago… i think another 100 would fit on easily and plug in that 3rd plug that is whispering my name each night my wife cranks up the A/C and i go sleepless watching the ‘GREEN LANTERN” battery gauge worrying about the engine coming on as backup at $4 a gallon in CALIforniA!! WHAT should i buy and can ya get just a panel w/o inverter and stuff that i don’t need? THX

Getting the panel should be easy. I believe on the current Travatos, the panels are made by ZAMP. You should be able to find one of their panels that will be plug and play with your system.

First off great article, I have been scouring the web looking for someone who can really break it down and tell me the best options for solar.

I am new to the RV life, I have a 2005 Lance truck camper. I plan to do mostly (if not all) my camping “boondocking”. I typically work 8-12 hour days 5 days a week so with solar it should get plenty of sun time. When in my camper I would like to run AC, charge/use cell phone, watch tv, and occasionally use an instant pot to cook with (I typically meal prep). How much solar wattage would I need to acquire? I don’t know exactly how large my batteries are (I am willing to upgrade).

Thank you for all your help!

On a typical RV, the AC,which is the largest single electrical load, will not run off of the batteries. The AC is a 120 volt appliance that is connected to run only off of the generator or shore power.

To run the AC off your battery bank, you would need a very large inverter (oversized to handle the current inrush during the AC compressor startup)- something around a 3000watt rating should handle it.

Assume 1800 watts for the AC and 6 hours of run time a day and that’s 15 amps times 6 hours or 90 amp hours. But the whole system is quite inefficient and to get 90 amp hours out of the system, you realistically need to assume a 60% conversion ratio. So dividing 90 by 0.6 equals 150 amp hours off charging input at the unrealistic nameplate ratings. As the article gave the daily output of a 100 watt panel at 8 amp hours per day, you’d need about twenty 100watt panels to just run the AC 6 hours on a perfectly sunny day. And now you can see why RV’s have generators.

What is the best way to connect an approx 3000 watt inverter. I am purchasing a 200 watt solar kit but how do i use AC 120v in my rv?

Uh…. with really big cables?

Seriously though, I’d recommend consulting with a professional RV or marine electrician in your area who can either survey your situation, or just do the job for you.

James- thank you for this article. It’s the most sane article I’ve seen for RV solar and it’s refreshing to see someone put the info out there just for the sake of helping others. While I’m not against affiliates, the internet is awash on sites that are really just affiliate marketing engines, and don’t offer anything helpful.

Glad you liked it!

It’s turned out to be a pretty popular article.

Hi James,

This has been one of the most helpful posts on RV solar I have found. I am buying a 2020 Jayco Seneca that is pre-wired with 8 gauge wire from the roof to the inverter. I’m hoping to get 1200 watts of panels because we plan to boondock for 2 weeks at a time. We also have an 8k Onan generator if needed. My question is; is that 8 gauge wire large enough to run 1200w of panels to the inverter?

You should be able to find a chart online that will give you the ampacity of a given wire or cable. My advice would be to over-build so that you have room to add if you want down the line. Plus, it’s safer.

You’ll need to know the nominal voltage of your panels in order to get the amps they might push.

James, great article in easy to understand terms. More importantly you provide real world examples rv folks can relate to. I’ve decided to go Lithium batteries for many reasons, but was struggling with configuring correct build out on my solar system to maintain them. I’m going camping first like you suggested. I’ll worry about solar build out after getting data you suggested.

Camping in the name of science!! I love it.

Enjoy it, and learn all you can!

This is a Rookie question I’m sure. My wife and I are retired, we decided to live at an RV park for 7 months a year in Florida. If the class C has some solar panels on top and Im plugged into the power at the site, Will I be using any of the power Im generating, or is the solar power stored in the batteries only used when unplugged ? Im running the a/c constantly i assume, but when I use the lights etc, doe the solar help me on the electric bill? Thank you. Most of the article was way above my pay grade, but I made it too the end and I appreciate your time

If you are plugged in, then you won’t really notice solar. I suppose technically it could cause you to draw a bit less juice from the pedestal, but unless your park charges for electricity by the watt-hour, you don’t really benefit.

Some of the RV parks in Europe charged for electricity this way, but we’ve never encountered one in the US. Maybe it’s different if you stay for months at a time.

Unlike a home, there’s no “net metering” with an RV.

Thank you, yes its water, septic, trash and lawn cutting, we pay for the electric used per month. If we stay more than a month electric,. is put in our names.

I followed your solar sizing method and am close to installing some panels on my Bigfoot TC. Before drilling the fibreglass roof, I have realized that perhaps my smokin’ hot deal on a pair of 160 watt panels was a mistake. Upon close examination I realize that the junction box on the back of the panels is rated IP65.

Are you able to comment on the wisdom of running these panels on top of a 70mph vehicle in heavy rain? I’m concerned that IP65 might not keep the water out.

Our Zamp panels are – I believe – IP66 rated. So just a little bit better.

If you think about how a solar panel is mounted though, it might not be such a big deal. The junction boxes on the panels are typically on the bottom. I don’t know about your panels, but on ours, the boxes do NOT extend below the frame of the panel. Which means that any water would have to bounce off the roof and back up to hit the box at all. I suppose turbulent air could carry some water up there as well. But in any case, it’s not like you’re putting the junction boxes on the grille of your vehicle and driving into a thunderstorm. I think you’d probably be OK. To be safe, I’d try to rig up some kind of mounting solution that you could replace the panel from if it ever went defective.

You have me rethinking solar power. I stay maybe three days at most usually and then off I go. So I need more battery power. I don’t use the air conditioner much here in the Pacific Northwest but I would like it use my microwave and TV. I have one lead acid deep cycle battery. Maybe I should add three more since I have room for that many. Will my truck charge all four while driving and will they last me long enough. Or should I buy a generator ? Oh and can I buy an inverter and go from the battery power plugged into my land line power socket? That would be easy. My trailer is a 2018 and has LED lighting.

If you have room for the batteries (and cargo capacity for the weight) then yes, I would add batteries before adding solar panels. They’re more useful in a wider variety of circumstances – like clouds in the Pacific Northwest!

If you wire them properly, then yes, your vehicle will charge four the same as it charges one – just perhaps more slowly.

I can’t say whether they’re enough, but you could go camping in the name of science to figure that part out.

Thank you for clarifying a lot of points I’ve been wondering about (cost of panels, how I use the system, tilt vs no tilt, etc) I think that if you were to harness the brain energy you’ve obviously expended on this subject you could probably run your air conditioner for a few days. I will say, however, that after researching the cost of your litium battery, extra alternator, inverter and such that you are waaay out of my league. Also, should it fail on the road at 2am like these things invariably do, I doubt I could walk into a Walmart or RV supply the next day and find a fix. That said, you have a really cool system. Once the price of lithium batteries, inverters and controllers come down out of the stratosphere I’ll be the first in line. Keep up the good work!

Same here. The last 1200 watt solar system I admired on a fellow rv’rs rig (w. 3 – 100 ah lithium batterys) cost a whopping $15,000 ! If the owner would have mentioned the price prior to the grand tour, I would have skipped the solar dream tour. 15 K ? !!!! A generator never looked or sounded sweeter. Great info here though on building a solar system.

Yo John… I think you got ripped off on your solar install. $500 for panels & misc, 3 battleborne batteries at $3000, Mppt Charge controller at $500 and misc wiring etc at $1000 and if you paid someone to install 3 days at $3000 it put you in at about $8000. Was this done at Camping World????

OK here is my situation. I am curious as to your thoughts. 2008 Majestic 29′ Motorhome. Most camping done on the western slope of Colorado. SUNSHINE New to this adventure. Unit has a single Group 31 105 AH battery and the tray does not have room for a second.

We have Onan 4000W generator to run the AC if we ever needed it. Typically I will leave on Friday come back on Sunday. I would be dry camping the whole time. The fridge would run off propane and a small amount of DC, Maybe if it rains we turn a small tv on for an hour. DVD player. Fluorescent lights — until I replace with LED…. Mostly its going to be the cool Colorado spring and fall nights. I’ll probably turn the heater on at 9 and ff at 7.

Could I get buy with a simple 200W portable unit and avoid making holes in my roof? Should I do a 400W roof mount or even more? Removing enough from these so they are not free links for Amazon.

https://amzn.to/2Z0432U

https://amzn.to/2X1o5Zp

Honestly, in your situation, I’d start with more battery.

I know you said there’s not room for any more, but if you were to go with a drop-in lithium replacement – that would effectively DOUBLE your battery capacity instantly. No worries about cloudy days.

From there (now that you’ve got enough juice to last at least a day), try the experiment in the article and see where you wind up.

I have a 24′ TT and a 100 watt Grape Solar panel with a Xantrex 35 amp controller. Question is why the panel won’t get my batteries as fully charged as my household current at home?

Most of our power use is just for lights, but when temps get down below freezing we use the heater and the fan apparently sucks down the power. When we start & batteries are fully charged from our household 120 v, the batteries last for several days under these uses, but once i’m down on the gauge, I need to use the panel every day. Even though controller says the batteries are full, they’re not as full as when charged up with 120 v.

Interesting.

I’d question whether the charging parameters are set properly for your battery. Are they adjustable?

The people at Xantrex said I need a larger panel, preferably above 9 amps That would be at least 180 watts w/a Grape Solar system. Sounds do-able, if necessary

Do many full time boon-dockers add a wind generator to their solar systems?

I’m sure someone has. Not us though. We don’t stay put long enough to make something like that worthwhile.

Thanks for you knowledge and honesty! Spoken from an engineering

not marketing perspective. My young son is an EE working for Toyota and I’m starting to understand how engineers think. 🙂

I’m a vacation RV’er using our TT for long weekends or 1 week vacations. I just want to go places that don’t have power pedestals and keep my 2 6 volt Trojans charged.

What do you know about the Renogy panels? The are comparatively inexpensive and I’d like to know why. I’m not one to buy cheep for the sake of cheep. I like quality but I don’t like wasting money either.

Thanks James! I’m a fan of your Youtube channel. Love your style…don’t change a thing.

Dan

Many people buy and use the Renogy panels without problems.

Though I haven’t used them myself, I think they’re probably a fine panel for the money based on anecdotal evidence from other users.

I like your tip about trying to conserve extra energy. That would make sense considering you don’t want to burn the energy you store. I’ll have to consider your tips so that solar works for me.

Great presentation, James! I might be getting this someday yet. I think of batteries like buckets, but they leak all the time and get less full… well anyway, it’s not a good analogy.

My goal is to be able to have breakfast without running the generator! I have an induction stove & a microwave to cook with, both require 110. Behind that goal, is to skip using the generator on days we don’t drive (several), as I don’t like the noise/pollution nor did I like other people’s generators when I didn’t have or need one.

1. I should have been more diligent getting a propane stove top. The induction works fine, but can’t use it without the generator or shore power. Almost everywhere we’ve camped since we got the van limits gen use to 10AM. Kinda late for breakfast. I have been using my old backpack stove, but when it’s windy or raining that’s a pain. So I missed my first goal from the get go.

2. In our camping test, we ran the batteries (2, 105Ah flooded 12V) down to 50% two nights in a row this week using lights, the small Truma fan (I assume it’s small, it makes 1/10th the noise of any of our other RV heater fans) a limited amount (set at 54F) AND the refrigerator. All of this on an early 2018 Crossfit. That compressor reefer is killing the battery I think. If there had been an option to get the old style cook top and propane reefer that’s what I would have chosen. I didn’t see propane reefers on any of the new vans of interest but a Popular from RoadTrek was the only thing we looked at with both propane options. We have 200W of solar and no inverter with our 210Ah of battery.

So right now I’m reading blogs and user sites to figure out what to do before spending more money. It looks like doubling the battery pack would get us through 24 hours, maybe. There are some high rated AGMs, I think one rated at 300+, so 2 of those would be over 600Ah. Don’t know the cost. Adding more solar might not help much, tho that’s the direction I was headed. 100 W panels (we have 2) are good for about16 Ah/hr in charging so it takes a long time to get to 210Ah, I see 12.8 hours on my calculator, but more like 6 to get the 50%, 105Ah needed as long as I keep the batteries above 50%. Oh my! Equator camping indeed! To charge 600 Ah is at least 1.5 days without any over daytime use or night time loss!

I still have a question about the capacity of my batteries, i.e. whether they are able to deliver the Ah they were rated for since they sat around for a year after the coach was built before I bought it. I might be dealing w/ limited capacity at this point. Need to find out how to determine that. I think there’s a load test for that but don’t know who to ask for the test. From what I have learned from others online my experience may not be that different. I think the builder (Coachmen) expected their B vans to be used from Point A to B each day w/ van engine alt charging to get thru the night, which it will. Or people will stop for extended time where they are plugged in. Boondocking requires generating it looks like…

So part of my question is about an inverter to run the induction cooktop which I think is 1400W about 10 minutes in the AM when my current battery is already at 12.0-12.1V. I think I need more battery and will that require a 2000W inverter?

I am in awe of your persistence on your tech pursuits, your writing clarity and your willingness to answer questions. Thank you!

Interesting saga there – but to answer your question… yes.

It sounds like you need more battery capacity for your style of camping and the rig you have. That’s problem #1.

Problem #2 is yes, you also need a larger inverter (if you want to run the cooktop wide open). I don’t know of any 1500 watt inverters off hand, but that might be cutting it close anyway.

A 2000 watt inverter would be enough to get you cooking.

Best of luck!

Regarding your concern about battery capacity and suspicion that you aren’t getting rated AH capacity: if your batteries are lead- acid and since they sat in a dealer lot for a year it is likely they were poorly maintained and developed some sulfation on the plates. This occurs over time and is accelerated by deeply discharging the battery, or by not fully recharging the battery to a full state of charge after partial discharge. “Equalization” is a charging profile that can reverse some levels of sulfation and recover lost capacity on degraded lead acid batteries, especially liquid cell batteries that require owner service, like most golf cart batteries. Sealed maintenance free batteries and AGM or gel cell batteries may be limited in the amount of equalization that can be performed, or it may be damaging to the battery, so check with the manufacturer for the proper profile and especially for restrictions. The high voltages used can damage some types of lead acid batteries or cause boil over, so read up on it first AND follow battery and charger manufacturer recommendations precisely.

I’m sorry but I want the horse in front of the cart. Batterys are the limiting factor. Once I have all the batterys I can: afford, carry, place I need to know how much solar is needed to safely ( for the batterys) to charge them as quickly as possible. Depending on battery type, change rates vary so no matter what I want to power I’m still limited by available battery amp hours.

Still the best article I’ve read to date!

True – on a day-to-day basis you’re still going to be limited by the size of your battery bank.

Lithium batteries offer the best electrical-storage-to-weight ratio. You’ll have to do your math.

Interesting factoid: On our lithium powered coach, I’m actually going to *remove* solar panels. Our alternator charges so fast, and our capacity is so large, that we don’t find solar gives us much.

Solar, for us, it mainly useful when the rig is in storage. That’s it.

Great article James,

I have a few questions. I live in a Step van in Santa Cruz. Currently been living In The van as a full time student for 16 months. I am getting really close to adding solar. I did t think I needed it but the longer I’m in the van the more I would like a few amenities. I ran my batteries dead once since living in the van( 2 x 12v deep cycle batteries ) using a regular battery inverter. Was charging a phone and a laptop all night, that’s all. Since then I worry about killing my batteries so I use them quite miserly.